There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Thu Apr 24, 2025

Approach:

Introduction:

• Ancient Telangana, rooted in the Asmaka Mahajanapada, developed a unique socio-cultural identity under the Satavahanas, Ikshvakus, and Vishnukundins—reflected through evolving languages, literary expressions, visual arts, and monumental architecture.

Body:

Follow a thematic structure, using subheadings as in the question. Each section should include:

• 3–5 concise points

• Examples (like inscriptions, literary works, sites)

• Brief interpretation or insight

A. Language

• Use of Prakrit by Satavahanas for public communication

• Rise of Sanskrit with Brahmanical revival under Ikshvakus

• Traces of early Telugu words in inscriptions (e.g., Adavi, Bapi)

• Widespread use of Brahmi script,• Multilingualism showing social inclusiveness

B. Literature

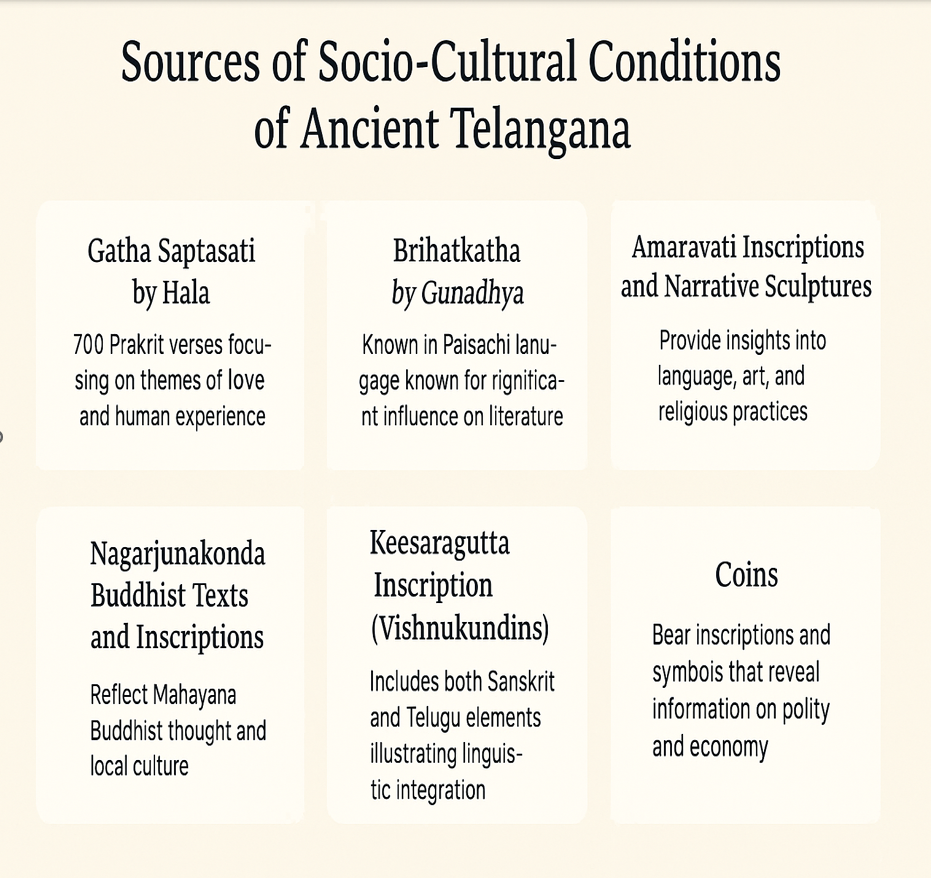

• Hala’s Gatha Saptasati in Prakrit highlighting rural life

• Influence of Gunadhya’s Brihatkatha on Indian storytelling

• Buddhist literary activity at Nagarjunakonda

• Narrative stone reliefs acting as visual literature

C. Art and Architecture

• Stupas (Amaravati, Bhattiprolu) as devotional-public spaces

• Urban culture in Nagarjunakonda blending civic and spiritual life

• Depiction of ordinary life in sculpture

• Early Hindu cave temples under Vishnukundins (e.g., Undavalli, Mogalrajapuram)

• Role of sites like Phanigiri and Nelakondapalli in cultural integration

Conclusion:

• Ancient Telangana’s evolution in language, literature, and art laid the foundation for its distinct cultural identity. This legacy shaped its medieval developments and reemerged in modern times, culminating in Telangana’s statehood in 2014.

Introduction:

“The land of Asmaka was where the Deccan began to speak” reflects that Asmaka, the only Mahajanapada from the Deccan, was located in the historical core of Telangana, where a distinct socio-cultural fabric began to emerge. The term Telangana finds early mention in the Tellapur inscription of Sangareddy, a region that later flourished under the Satavahanas, Ikshvakus, and Vishnukundins in language, literature, art, and architecture.

Body:

A. Language:

1. Prakrit as a Popular Language of Communication

a) During the Satavahana rule, Prakrit was widely used in inscriptions and official communication.

b) It made administration more accessible to the general public, showing how rulers connected with commoners.

2. Sanskrit – Language of Rituals and Scholarship

a) Under the Ikshvakus and later the Vishnukundins, Sanskrit started replacing Prakrit in religious and elite circles.

b) This shift reveals growing influence of Brahmanical traditions and a divide between learned and popular language.

3. Emergence of Telugu as a Spoken Identity

a) Inscriptions from places like Jaggayyapeta and Phanigiri included words like Adavi and Bapi, showing the local Telugu language was gaining ground.

b) It highlights the beginnings of a regional identity rooted in native speech.

4. Brahmi Script – Tool for Communication

a) All three dynasties used the Brahmi script, found in inscriptions across Telangana.

b) This points to an expanding literacy and a need to record land grants, religious donations, and messages for public awareness.

5. Multilingual Coexistence Reflecting Social Pluralism

a) Prakrit, Sanskrit, and early Telugu coexisted, often within the same regions.

b) The Chikkulla inscription, with the Telugu word ambul, reflects how the spoken language of the people entered formal texts.

B. Literature:

1. Gatha Saptasati – Rural Emotions in Poetry

a) King Hala’s Gatha Saptashati is a collection of short Prakrit poems about love, longing, and life.

b) Uniquely, many verses speak from a woman’s point of view, offering a glimpse into rural sentiments and social life.

2. Gunadhya’s Brihatkatha and Popular Storytelling

a) It was Written by Gunadhya, though now lost, Brihatkatha deeply influenced later works in both Sanskrit and Telugu like i. Somadeva Suri – Kathasaritsagara

ii. Kshemendra – Brihatkatha Manjari

iii. Harisenā – Brihatkathakosha

iv. Varahamihira – Brihat Samhita

b) It probably started as oral storytelling, which later helped shape classical narratives across languages.

3. Nagarjunakonda – A Buddhist Knowledge Hub

a) Under the Ikshvakus, Nagarjunakonda became a place for learning and literature, especially for Buddhist monks.

b) Pali and Sanskrit commentaries written here were meant to teach spiritual and moral values to all, regardless of caste.

4. Stone Sculptures as Storybooks

a) The carvings at Amaravati and Nagarjunakonda weren't just decorative — they told stories from the Jataka tales and epics.

b) This was a way to teach values to those who couldn't read, keeping stories alive for the entire community.

C. Art and Architecture:

1. Buddhist Stupas as Public Devotional Spaces

-Buddhist stupas at Amaravati, Bhattiprolu, and Salihundam were built to honor Buddha’s relics and teachings.

-They weren’t just religious but they also became community spaces where people gathered, prayed, and shared stories.

2. Social Integration through Major Sites

-Places like Nelakondapalli, Phanigiri, and Dhulikatta weren’t just archaeological sites — they were crucial centers of spiritual, social, and trade activity.

-They brought together monks, traders, artists, and pilgrims in shared spaces.

3. Art that Spoke to the People

-Satavahana and Ikshvaku art didn’t only show gods, it also showed ordinary people, trees, animals, and symbols everyone recognized.

-This grounded their architecture in real life and made spiritual messages feel personal.

4. Nagarjunakonda – A Planned Cultural City

-More than a religious site, it had monasteries, water tanks, halls, and inscriptions — it was a complete urban setup.

-It reflected how religion, education, and civic life could blend in one place.

5. Cave and Temple Architecture under Vishnukundins

-The Vishnukundins built cave temples at places like Mogalrajapuram and Ramatirtham, often with images of Shiva and Vishnu. Also built Undavalli caves and Akkanna -madanna caves.

-These spaces show the shift towards Hindu temple worship and also reveal how artistic and religious ideas evolve

Conclusion:

The socio-cultural roots of Ancient Telangana—seen in its language, literature, and architecture—shaped a distinct regional identity. This legacy continued through medieval dynasties like the Kakatiyas and ultimately contributed to the formation of Telangana as a separate state in 2014, reaffirming its long-standing cultural individuality and historical continuity across centuries.

Additional Embellishment: